By kate, on February 7th, 2011 My youngest brother decided to go to school. He was fifteen. He said he needed more structure. He wanted a teacher to tell him what to do. When Mom told him what to do, it made him angry.

It was a little shocking, that he’d even think to go to school. I hadn’t gone. My middle brother hadn’t gone. We stared at Gabe uncomprehendingly for a moment. Mom wasn’t thrilled with the idea, but she heard him out, and my parents talked it over a lot, and then they signed him up at an arts and music charter school in Trenton.

Off he went. I was already in college, so I wasn’t there to witness the day-to-day transition.

It was a little shocking, and then it wasn’t. Then it was just normal. After all, school had always been a option for all of us. To me, school seemed like giving up. Like giving in. When homeschooling parents got really scared, they sent their kids to school. When they didn’t believe in themselves, and they started to listen when their friends’ whispered skeptical little questions about science lab. When kids got scared, they went to school. When they didn’t trust themselves enough. When they’d met too many school kids who looked at them funny, and they felt left out.

But then Gabe went, and it wasn’t the same. No one had given up. He had made his own choice, and he chose school. He defected so smoothly, that I had to remind myself that he was a school kid now. That when people asked, “So you were all homeschooled?” I had to say, “Well, my brother is in high school now.”

Continue reading Gabe goes to school

By kate, on February 3rd, 2011 I think maybe I’m not anymore.

But I was an experiment.

No one was really sure how homeschooling would work out when my parents decided to give it a go. I mean, there were a few kids who had made it through, like the Colfaxes up on the farm in Northern California, who trotted off to Harvard after mastering all that goat herding and fence building. I don’t think my parents expected me to go to Harvard. Actually, I know they didn’t.

(This picture makes me really jealous of the Colfaxes. source)

I am the first born. It sounds a little epic when you write it (and when you put it in bold). Like there’s probably a prophecy somewhere about me and how I’ll save the world from Voldemort or something. Which I feel like there probably isn’t, because I haven’t had to learn any magic yet, and I’m getting kinda old for that sort of thing.

My brothers had it easier. By then, it seemed like homeschooling was working reasonably well, even though there was no real evidence that I had learned any math.

I am very cutting edge. You know, I’m part of a tiny group of grown unschoolers who are out in the world, doing stuff. Being people. Succeeding wildly. OK, maybe not that last bit. But I’m not sitting for hours on end in Grand Central Station, either, staring at the enormous clock in the hopes that eventually I’ll learn to tell time.

We used to make fun of each other (us homeschoolers), saying, “Can you tell time yet? Can you tie your shoes?” We were aware that everyone expected there to be big, obvious gaps in our educations. Even our parents thought there might be. Because we were an experiment, and no one could really be sure what would happen.

Continue reading I was an experiment

By kate, on February 2nd, 2011 Sir Ken Robinson is really funny. Listening to him talk about education is a little like watching a comedy routine. I wish I had a British accent. If I had a British accent, I’d be so much funnier. My favorite thing about people with British accents is that they can make noises that count as words. They’ll just trail of and go, “Hummghhrrawwhhj….” and that will count. It will even sound good. People with American accents can’t do that. We have to use words constantly. It’s very limiting.

Anyway, Sir Ken Robinson gave an amazing talk called “The Element” for the Aspen Institute that is worth watching, if you have a free hour and are willing to sit through an incredibly long, fabulously entertaining and mostly unrelated introduction to the topic. When he eventually makes a point or two, they are awesome. He talks about how people rarely do what they love with their lives. They are rarely in their element. And that is a huge waste of human talent and potential. He talks about ADHD and compares it to the rash of tonsil removal procedures that were so popular when he was a kid.

(I like him. source)

But my favorite thing that Robinson says is that the paradigm needs to change. The paradigm of school. It’s broken. I believe that. And I feel nervous about saying it, because I didn’t go to school. I feel like I’m not allowed to say it. So I carefully say things about how both school and, um, un-school have things going for them. I do think that. But I also think that school is, in general, a lot worse. Not because it is impossible for school to be great. But because the way school works now is so systemically, structurally, integrally flawed, that it needs a revolution.

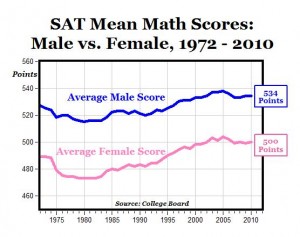

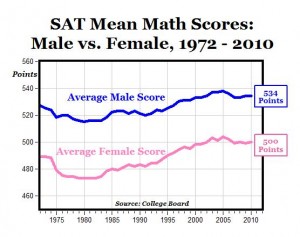

Robinson critiques the idea of reform. Reform relies on the notion that the system, as it is, is inherently fixable. It just needs some tweaks. It just needs some smoothing out of a few kinks. Does standardized testing count as a kink? What about dividing children into grades? These are basic sorting devices that many people who talk about these things believe the school system cannot exist without. Yet they are really pretty arbitrary. It’s hard to think that something so big and so old might be arbitrary. It’s disturbing. Some kids do well on standardized tests, but most do not. Most kids, despite the fact that they take tests regularly, never seem to get “good” at taking them. Social psychologists love to do experiments where they prove that when non-white kids or girls or anyone who is different in some way from the normative identity is reminded of their differences before taking a test, they do worse on it than when they aren’t reminded. Some kids are reminded of their differences every day. Standardized tests don’t sufficiently prove anything about intelligence, competency, or capability. They do conveniently sort children into more manageable groups.

(enough already. source)

Continue reading Revolution is necessary

By kate, on February 1st, 2011 I finally started reading Bird by Bird. Obviously, I should have read it about five years ago. Possibly more. I’m a writer, after all, and Bird by Bird is THE book about being a writer. Anne Lamott unites writers everywhere through her self-deprecating, reassuring descriptions of us as a mentally unstable, tormented, and chronically insecure bunch. We have a lot in common. We believe that publication will save us. We worship the false god of perfectionism until we are driven to insanity. We imagine that other, published, writers get everything right on the first try. We pay close attention to our lives and to the lives around us. We have a special relationship with the sprawling, unfocused world. We bring it into focus, little by little. Bird by bird.

(source)

It’s all very flattering, to imagine myself in the company of Anne Lamott as I freak out about my latest assignment and wonder how it was that at some point I was able to delude myself into imagining that I could write. The last sentence, for instance! All of the words should be rearranged! And this from someone who JUST wrote a piece about learning how to write. It’s disgusting.

Anne Lamott is soothing. Sure, she got her first book published by Viking at twenty-six (TWENTY-SIX!), but it’s OK, she and I are really completely alike.

She tells her class, and her readers, to start small. To think back to the things that we all have in common. To write first about kindergarten, then about elementary school. To work up through the grades. This is where we should all begin.

Continue reading Bird by bird

By kate, on January 31st, 2011 People ask me how kids will know how good they are at something without tests. It’s a question I get a lot. Possibly because I go through life saying things like, “Can you believe how many tests kids have to take? How much better would the world be if they were drinking milkshakes instead?”

Milkshakes are so good.

OK, I don’t really think kids should drink milkshakes ALL the time. But I think they’d be better off drinking them than taking tests. Especially if they are chocolate peanut butter milkshakes.

I’m a little sad right now, because my mom just gave me this huge lecture about how I need to stop drinking so much diet soda, because it’s definitely going to kill me. I don’t remember why. Calcium was involved. Maybe my bones are going to turn to dust really soon. And diet soda was my healthiest option, since water tastes completely boring to me. She doesn’t know how close I am to drinking milkshakes all the time.

(Vanilla peanut butter is pretty amazing, too. Source)

But that’s not the point.

People explain to me how important tests are, for the kids. They emphasize that part. For the kids. You know, rather than for the maniacal pleasure of power-drunk adults who think tests are hilarious? Pick C., sucker! Fill in the C bubble on #29! You know you want to! DOO IT!!!!!!!! Actually, they mean rather than for maintaining the balance of society, which, they are pretty sure, tests are also good at.

I love the question about kids and tests. Because it’s really easy to answer. Which makes me feel smart.

Continue reading But how will kids know?

By kate, on January 28th, 2011 This is a guest post from Kaamna Bhojwani-Dhawan, CEO and Founder of Momaboard.com, the social network for globe-trotting children and their parents. I love the idea of travel as education. When I was fourteen or so, my dad wanted to buy an RV and spend a year traveling around the country as a family. He thought that would be the best homeschooling education his children could possibly receive. My mom said no. And I’m glad I didn’t have to spend a lot of time in an RV with two incredibly exuberant, shockingly loud brothers. But still, it was a pretty awesome idea. Thank you so much for this post, Kaamna!

I moved to America from India to go to college. I left my home, my family, my comfort zone to move to an environment that was culturally and socially radically different from what I knew. And I was one of the luckier ones – I had visited the US before, spent some time in London and had a fairly good idea of Americanisms from shows like Beverly Hills 90210 and Full House (it was the ‘90s!). Some of my fellow international students had left home for the first time, and the formidable cost of a round-trip ticket meant that they weren’t going to see their families for four years, at least.

The decision was our choice – we voluntarily made this move, looking for better education, exposure, opportunities that we couldn’t get back home. Yet, we always marveled at our American counterparts despairing at the university gates when leaving their parents who lived in the next state! Or the ones that walked around with brave faces when their parents were unable to send them care packages at exam time. We routinely compared the ignorant questions we heard on a daily basis: “Oh your parents probably can’t listen to the CD you recorded because you don’t have CD players in India”, or “Isn’t Nelson Mandela the President of Africa?” The difference between them and us was not that we were experts in world history; it was that we had been exposed just enough to see that what we know was a lot less than what we didn’t know. And that kept us humble and hungry in our quest for knowledge and experiences.

Continue reading Life lessons from the world’s classroom

By kate, on January 27th, 2011 This is going to be shocking, so please hold on to something steady: kids learn at different paces.

Wait, there’s more…They learn from doing things, rather than just being told how to do things.

And here’s the most terrifying, overwhelming part: they don’t really need to be “taught.”

Lisa Nielsen, the well-known education and technology expert, writes about how problematic standardized reading tests are. They fail to measure how well a student will be able to read (which is usually quite well, given some time and support), and instead place enormous amounts of pressure on students to be at the same level as their peers, even when we have plenty of information about how the factors that influence when students will begin to read fluently have nothing to do with the classroom.

And what about writing? Nielsen worries that too much emphasis is being placed on formalized written communication. She suggests that writing doesn’t feel relevant for students, because their projects stay within the classroom, rather than relating to the world outside it. They could be writing blogs and columns and letters to the editor. But they write essays that begin with a thesis statement, are followed with two points in defense of the thesis, then a counterpoint, a summary, and a neat conclusion.

She asked me how I learned to write. Which is something I remember much better than I remember a lot of things that happened that long ago.

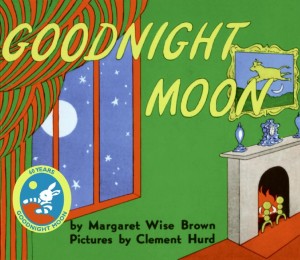

But first, this is how I learned to read: my parents read to me. All the time.

(My dad was a pro at reading this one. source)

Books were exciting and mysterious and magical. I don’t know a single unschooled kid who didn’t learn to love reading. We learned at different ages, of course, but no one had to take a test, and so no one got left behind.

Continue reading Learning how to write

By kate, on January 26th, 2011 The last installment I’ll be sharing here of the thrilling memoir I wrote at sixteen. For chapter one, click here. For chapter two, click here. I don’t always remember my teenage self fondly, but she seems pretty decent in this story. And her name is Fern.

In the car on the way back from the coffee shop Mom wants to discuss my life. Specifically my education. Her favorite topic. I’m so exhausted from my coffee shop ordeal I can hardly keep my eyes open. She’s mentioning geometry a lot. History, too.

“… Responsible for at least a complete public high school educational equivalent,” she’s saying very seriously, glancing over at me. I’ve heard it a lot. I nod several times.

“I’ll have to start assigning reading,” she says.

“Ok,” I say. We both know I’m not going to pursue history all the way to the library myself.

“You have three credits in writing already this year, you need to focus on some other subjects. Such as geometry, history, and chemistry.” I record the amount of time I spend doing stuff on a chart, so that we can calculate how many and which credits I would be receiving in the school system. Colleges like that stuff. Apparently they don’t like it when you get more than one credit per subject a year, though. They think you’re lying if you show up with more than seven credits for any one high school year. I got twelve last year, a lot of them music and writing. Now Mom’s trying to figure out how to divide the stuff I like to do into littler categories, like composing, classical studies, and performance for piano, and poetry, short story, and novel for writing. And she wants me to “focus on other subjects.”

“Uunnggghhh…” I groan loudly, unable to stay agreeable any longer. Mom takes this in stride and begins listing her new idea of my daily schedule. “Get up before ten,” it starts. I stop listening. It’s unrealistic. I wonder if she knows by now. She never seems to. Every month or so she has a new idealized homeschooling dream plan. She makes me write lists, draw up charts, talk everything over again. Then we both forget about it a few days later and I’m back to writing poetry and she’s back to her life.

* *

Back home, I swear if the chin of the woman I’m painting does not begin to resemble a chin within three seconds I will coat the entire canvas with mars black and leave it. It’s Tuesday. Max is whining about math downstairs. He keeps complaining about geometry and I really don’t want to hear it because I feel somehow that this is a personal area and not something I want to share with my ten-year-old brother. I have to constantly resist the urge to test his knowledge against my own. I’m afraid if I do I’ll come out humiliated, and besides, I should be encouraging.

Abel and his friend Walker are playing Bach and they sound bored. They sound effortless for a while, then Abel botches a trill, Walker pauses a fraction, and I hear them telling each other they are idiots. Abel’s voice is clear and high, Walker’s low. They are in the music room below my bedroom.

“Sounds wonderful, boys!” cries Mom enthusiastically from geometry with Max. She’s always all bright and piping about music. I growl at the canvas.

“When is the concert?” asks Mom.

“Never!” yells Abel.

Continue reading Chapter 3: What SAT?

By kate, on January 25th, 2011 Another chapter from the thrilling memoir of my (um, a girl named Fern’s) life as a homeschooled 16-year-old. The names of my family members have been changed to protect their privacy, it seems. My brothers real names are Jake and Gabe 🙂 I’ll leave the boyfriend a mystery.

Abel, my younger, not youngest, brother, tells me that my boyfriend Drew has called three times. He also mentions that the chamber orchestra has called for him and wants him to tour with them as their soloist this coming spring. Abel plays the flute and he is great at it. He isn’t thrilled about touring, though.

“Where will I stay?” he says into Mom’s hair as she hugs him.

“I’m so proud of you,” Mom says. “What a wonderful opportunity!”

“Mom,” says Abel, who is thirteen but huge, “Will I have to stay in hotels by myself?”

“No,” says Mom, “of course not. We’ll all come with you.”

Max, my youngest brother, groans loudly. He’s sprawled over three dining room chairs, his upside-down face set in a grimace. “Nooo…” he elaborates. “I’m NOT going.”

I walk over to him and poke his stomach. I’m in a poking mood. He shoots upright, yelping, “Stop it, Fern!” He pokes me back. Max is not impressed by Abel’s accomplishments. He’s slept through concerts.

I hug Abel, too, since Mom has finished.

“Awesome, bro,” I tell him. “You rock.” Abel is one of my favorite musicians. (Another several including my father, Max, Ella, and some famous musicians.)

“Aw,” says Abel modestly. He doesn’t pretend, he’s actually too dumb about his skill not to be modest. “Whatever. It’s not a big deal.”

I slap his back. Abel is the only person I know who I can hit with all my strength and not have the least effect on. Believe me, I’ve tried. He doesn’t even blink.

Dad is sautéing stuff in the kitchen. He yells to Mom that he’s seen this coming a long time, and of course Abel’s getting a break like this. After all, he’s a damn good flutist. Mom agrees. Max pokes my arm. Ten-year-olds never know when the game is over. I rub his hair and he ducks away.

“What did Drew say?” I ask Abel.

Abel smirks. He hates Drew. “Hey, Abe-man,” he says in a corny Drew voice. “Your sister ‘round?”

“Yeah, what else, besides that, I mean.”

Abel frowns, thinking. “He’s pining away without you and he wants you to call him. I told him you were dead, but he didn’t buy it.”

I roll my eyes. “Thanks Abey.”

We make awful faces at one another.

Continue reading 16 and homeschooled, chapter 2

By kate, on January 24th, 2011 Two nights ago, I found pieces of an unfinished loosely fictionalized memoir about my life on my computer. I was sixteen when I wrote it. My name in the pieces is Fern. I guess I thought that was a really cool name. I actually still kind of like it. People always ask me what I did every day, as an unschooler. And I never really remember. When I read this stuff, I got a better idea. So I thought I’d share. Also, you can think about how much I’ve improved as a person and a writer since than, and be impressed. Or think about how little I’ve changed and wonder what that says about me.

Here it is (at least some of it):

My only piano student is seven-years-old. Her name is Eve. I like the name Eve and I’ve also found symbolism there, because she’s my first student and Eve was the first woman. Stretching it slightly, I admit, but I always do. Eve is playing “In the Canoe,” and she’s singing the words they have under the notes. Her voice is really tiny. All of her is tiny. I tell her to put her hand over mine and feel the hand position. She does. I say, “We are strong pianists. We have strong fingers. Wimpy fingers aren’t allowed.” She smiles a little, concentrating. I can’t help thinking, even though I’m her teacher and I’m supposed to be all encouraging, that her hands are just too small. There’s no way this kid can play. A single key could fit two or three of her skinny brown fingers.

“Come back in a couple years,” I think.

“Your turn!” I say in my teacher voice. She really buys it, this teacher stuff. I can’t believe I sound like this. Nice, grownup, but so cheesy!

“Ok,” she says cheerfully, and plops her hand down on the keys, a complete wimp hand. No knuckles to be seen.

“Hmm,” I say carefully. “Is that a strong hand?” I get the feeling she thinks it’s quite strong enough for her, but she shakes her head slowly, responding to my tone.

“How can you make it strong?”

She lifts her elbow several inches, giving her form a sort of crooked, broken look.

I try to remember being seven. Eve has the longest eyelashes I’ve ever seen. I rearrange her hand.

“That’s confusing for me,” she says. I stare at her blankly a moment.

“Oh? How come?”

“It just is because my hand is different from that and in the canoe piece…” her voice fades to an earnest mumble. I nod understandingly.

“I see, well, let’s try again.” I remember instantly that my own teacher told me never to use the word “try” in lessons, because it alludes to the possibility of failure, and creates an atmosphere of testing. Instead, I’m supposed to say “play.”

Continue reading 16 and homeschooled, Chapter One

|

A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

|